Recreating the 8th Southland Infantry Company at Gallipoli 1915.

I first heard about the 8th Southland Infantry Company uniform replication project towards the end of 2013, when Dr Aaron Fox (the driving force behind the Kia Mate Toa: Fight Unto Death – Southland at Gallipoli 1915-2015 project) asked if there was anybody who wanted to take up the challenge of recreating the uniforms worn by the 8th Southland Infantry Company at Gallipoli in preparation for the 100th anniversary in 2015.

When I thought about, I knew it would be a big task, but what was exciting was that the replication project was going to be attempted here in New Zealand with a good deal of the work being done in Southland.

In this part of the website we will illustrate the steps we have taken to recreate these garments a century after they were first made.

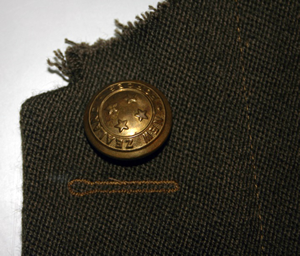

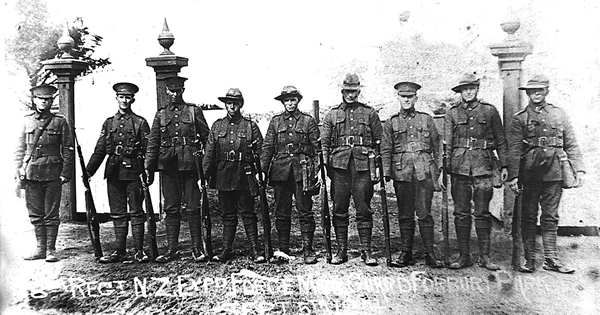

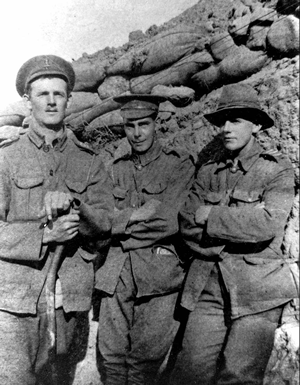

8th southland- replica uniforms

8th southland- replica uniforms