Chapter 4: Distribution

On 3 July 1919, Brigadier-General Richardson asked the Director of Equipment and Ordnance Services (D.E.O.S.) to ‘set aside two huts at Trentham Camp for the storage of war trophies and material.’[1] Richardson then contacted Major-General Robin, asking whether or not a National War Museum would be formed, and which Government Department would be responsible for the storage and allocation of these trophies. He still believed that a National War Museum would be created, and suggested that a National War Museum Committee be formed ‘to carry out the necessary administration.’[2] After a discussion with Richardson, J. Hislop, the Under-Secretary of Internal Affairs, and Dr J. A. Thomson of the Dominion Museum, General Robin passed the matter of the National War Museum on to Sir James Allen.[3] Allen, in turn, passed the matter on to the Minister of Internal Affairs.[4] A War Museum Committee was finally formed with the approval of the Minister of Internal Affairs, but the volume of captured material arriving in Wellington meant that the museum authorities could not cope with it all.[5] At its inaugural meeting, the War Museum Committee decided to establish a ‘special War Trophies Sub-Committee’, to deal with ‘the proper distribution of war trophies… to Museums and local bodies throughout the Dominion.’[6] Such a distribution was evidently becoming an urgent matter, as, apart from a temporary display of field guns outside the Wellington Town Hall, few trophies had been distributed and the Government had been ‘attacked for bringing out so many guns already.’[7]

Lieutenant H. T. B. Drew, the Officer in Charge of the War Records Section in Wellington was very conscious of his ‘historic task’. He suggested to General Richardson that a list be compiled of all war trophies which had arrived in New Zealand, together with a list of applications which had been received for trophies ‘in order that the whole matter of trophies be brought up to date.’[8] These lists were necessary so that the Commanders of the Military Districts could confer with the Mayors in the various Regimental Areas regarding the ultimate disposal of all the trophies arriving in Wellington.[9] On 9 September 1919, Mr G. J. Anderson, the Member of Parliament for Mataura, asked in the House whether or not the Government would ‘make arrangements by which every town in the Dominion which has a local governing body may have a share of the war trophies won by our soldiers during the Great War?’[10] Allen replied that it was impossible to state how wide the distribution of trophies would be until all of the trophies arrived from England. The claims of every part of the Dominion would then be carefully considered.[11] On 17 September, Mr Parr, the Member for Eden, asked Allen if trophies could be allocated to the public museums in Auckland, Christchurch and Dunedin?[12] Allen assured Parr that ‘every consideration’ would be given to his suggestion.[13] These statements effectively ended the National War Museum scheme, as the War Museum Committee was now superintending the War Section of the new Dominion Museum. It received ₤100 from the Internal Affairs Department vote to enable it to collect and purchase ‘suitable historic relics such as documents, war medals, uniforms, pictures etc.’ for the museum.[14]

In November 1919, Lieutenant Drew reported that the Ordnance Department was storing the captured war material as it arrived in the country, whereupon it was catalogued ‘in preparation for the time when it can all be handed over for distribution purposes.’ Drew believed that this system was working well, as far as applications for trophies were concerned, given ‘the absence of any rancorous debate on this matter in Parliament or in the newspapers’, but suggested that as ‘much material is yet awaited, it would be wise to allow matters to remain in status quo until after the elections.’[15] On 25 November 1919, Drew was replaced by Lieutenant V. G. Jervis as Officer in Charge of War Records and Trophies in New Zealand. Jervis was also appointed as the permanent secretary to a Central Committee established at Defence Headquarters in Wellington, consisting of the various Officers in Charge of Intelligence, Supplies, Administration and Finance within the Army. The committee’s purpose was to ‘deal with all questions connected with War Records, Base Records, Histories and War Trophies.’[16] A General Headquarters Instruction was then issued, outlining the distribution procedure to be followed for trophies. Those war trophies definitely identified as having been captured by a particular unit would be forwarded to that unit’s Headquarters for distribution. The rest of the trophies would be pooled, and after the Dominion Museum had selected suitable items for display, the balance of the weapons would be allotted to various districts on a pro rata basis. The Commanders of the four Military Districts were thus to ‘set up District Committees of all Expeditionary Force Commanding Officers in their Districts, to make final distribution.’[17] By 22 December 1919, the majority of the N.Z.E.F.’s trophies had arrived in Wellington and Lieutenant Jervis was requested to supply a list (in quadruplicate) of ‘1. All trophies received in New Zealand and which are Regimental property. 2. The remainder of trophies received’, together with a list of ‘all applications received from local bodies for allocation to their District of war trophies.’[18]

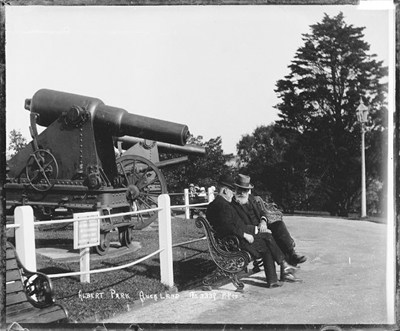

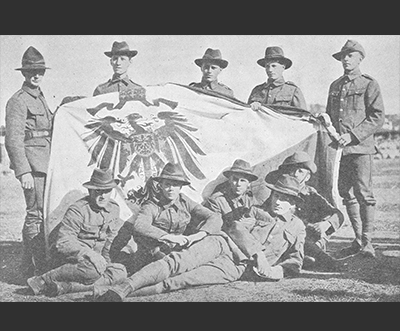

Throughout 1919, troopships were returning to New Zealand with the approximately 90,000 troops demobilised from the N.Z.E.F., who now required to be reabsorbed into New Zealand society. As the disabled and the shell-shocked arrived back home, the true cost of the war began to be fully realised by the New Zealand public.[19] To compensate for those who did not return, some sense of purpose had to be found for the war, to ensure that they had not died in vain.[20] This need to justify the enormous loss of lives was reflected in the dramatic increase in applications for war trophies made by Borough Councils, Town Boards, Patriotic Societies, Peace Committees, Schools, and even the Cook Islands. Defence Headquarters had received 27 applications for war trophies in 1918, while in 1919, 94 applications were received for suitable enemy weaponry, preferably field guns, which could be placed on public display.[21] By 1920, plans were being made for a National War Memorial (rather than a National War Museum) in Wellington, to ‘embody the objects and sacrifices of the war, and the virtues displayed therein in such a way that they will be an education and an inspiration not only to the present but to future generations, and so be of immense influence in the formation of the New Zealand national character.’[22] Following a tradition virtually unchanged since the Classical Age, the enemy weaponry captured by the N.Z.E.F. would now be symbolic of New Zealand’s sacrifices in the war. Those already familiar with the nineteenth-century ordnance in situ throughout New Zealand, believed that silent German artillery would be appropriate to stand guard beside the nation’s memorials to its war dead, keeping the memory of the war alive.

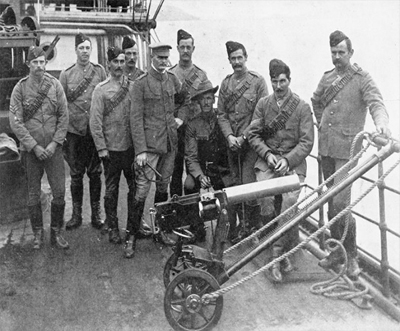

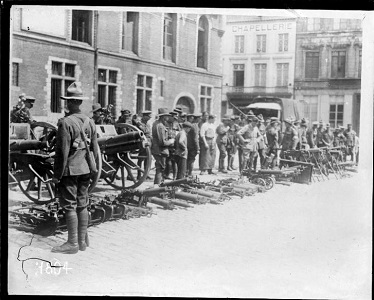

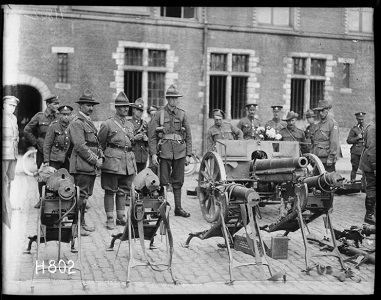

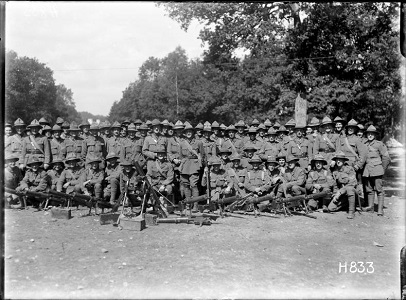

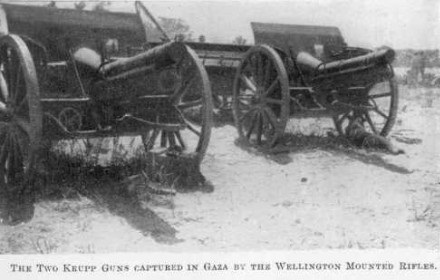

In January 1920, Lieutenant Jervis forwarded the required lists of war trophies and applications to Defence Headquarters.[23] The efforts of Majors Gambrill and Westmacott, and Captains Lewis, McClure, Self and Rhodes had resulted in 1,504 German machine guns, approximately 200 field guns, 81 trench mortars, and numerous smaller items having been shipped back to New Zealand as trophies.[24] Given the absence of any definite policy statement by either Major-General Robin or Sir James Allen regarding the ultimate fate of the N.Z.E.F.’s war trophies, these officers had obtained the best possible collection of enemy weaponry in the circumstances. It was obvious, however, that there was an over-supply of machine guns and insufficient artillery pieces. Unless German machine guns were specifically requested, the applications made to Defence Headquarters were for field guns suitable for display beside war memorials.[25] As the planning and construction of these memorials had commenced throughout the country early in 1920, there was pressure on the Defence Department to begin the distribution of trophies as soon as possible.[26] A secondary consideration, which had troubled Allen since 1916, was the recognition of the relative importance of regional cities, towns and districts. If field guns had provided Renaissance towns with a sense of security, in post-war New Zealand the proportions of trophy weapons distributed at the behest of the government signified (and in some cases enhanced) the status of respective regional settlements. While the numerous war memorials now appearing throughout the Dominion were expressing the sentiment “Lest We Forget"?, the fear amongst local authorities was “Lest We Miss Out"? in the forthcoming distribution of trophies.[27]

Sir James Allen resigned as Minister of Defence in 1920, to replace Sir Thomas Mackenzie as New Zealand’s High Commissioner in London.[28] He thus avoided the complex question of how to ensure that local sensibilities were not offended, once the distribution of war trophies began.

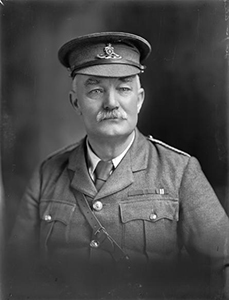

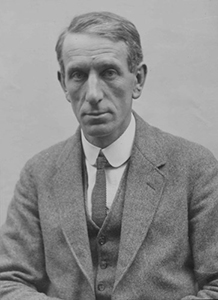

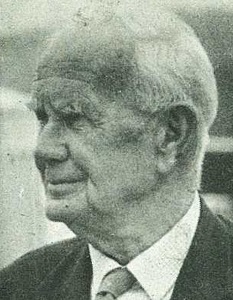

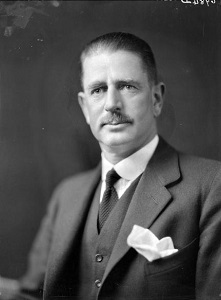

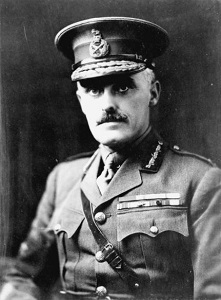

The Rt. Hon. Joseph Gordon Coates

Allen was replaced by the Honourable J. G. Coates, who became the Acting Minister of Defence. Coates immediately faced a question in Parliament from Mr E. Newman, the Member for Manawatu, who asked if the trophy committees established in the four Military Districts would consult with the Members of Parliament who represented the surrounding districts?[29] Coates agreed with the suggestion, and ‘thought that honourable members should be consulted in regard to the allocation of war trophies.’[30] The Defence Department, meantime, was reverting back to a peacetime establishment, with the associated reduction in personnel and funding. The burden of ensuring an ‘equitable distribution’ of trophies throughout the Dominion appeared to fall to the military authorities, who were discovering that in many ways the peace was proving more difficult than the war!

General Richardson, who was still primarily concerned with financial considerations, asked the Minister of Defence who would pay for freighting all of these trophies to City and Borough Councils. By 31 March 1920, the war had cost New Zealand ₤76,956,826, and the extra ₤5,000 which would be spent in freighting these weapons throughout the country was, according to Richardson, an unfair burden on the Defence Department.[31] He thought it unlikely that local authorities would be agreeable to meeting this cost, and recommended that the necessary funds be drawn from either the Internal Affairs Department or the War Expenses vote.[32] In his secondary capacity as Chairman of the War Museum Committee, Richardson presided over a committee meeting in June 1920 which decided that freight costs on trophies other than Regimental property would be met by the Internal Affairs Department.[33] The Defence Department would thus pay for the N.Z.E.F.’s official trophies to be distributed. The Internal Affairs Department, on the other hand, would pay for the national distribution of material no longer required for a National War Museum, now that a new Dominion Museum incorporating war displays was planned instead.[34] Even a display of trophies within the Dominion Museum became increasingly uncertain, however, when the Director discovered that such weaponry took up space needed for Maori war canoes and art exhibitions.[35]

By July 1920, there was widespread dissatisfaction amongst the County Councils and Town Boards throughout New Zealand that they were not represented in the War Trophies Committees formed in the Military Districts. General Richardson contacted the Commanders of the four Districts and asked them if they had any objections to the inclusion of these local bodies on the War Trophies Committees?[36] The composition of the regional War Trophy Committees became even more important when Defence Headquarters decided to delegate to them the allocation of all classes of trophies.[37] The Commanders of the Auckland and Canterbury Military Districts thought it was a good idea to include County Council and Town Board Chairmen, while the Wellington and Otago District Commanders were opposed to the move.[38]

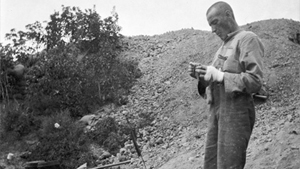

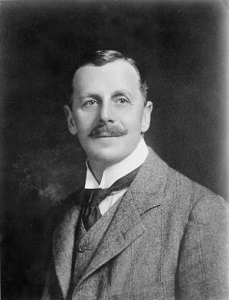

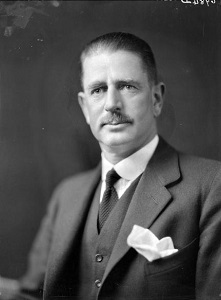

The Hon. Sir Robert Heaton Rhodes

The new Minister of Defence, The Honourable Sir R. Heaton Rhodes, soon found himself in the centre of a minor political furore. On 11 August 1920, he was asked in the House by Mr Burnett, Member for Temuka, when he intended to set up local committees to allocate war trophies, how these committees would be composed, and the lines on which the trophies would be distributed.[39] Rhodes replied that the committees had already been formed, but that Chairmen of County Councils, Town Boards and Road Boards were ‘to be given an opportunity of securing representation on the committee[s].’ No distribution was possible until all of the trophies had arrived in the country, whereupon ‘each committee should be supplied with a complete list of trophies belonging to the regiments concerned and could therefore carry out an equitable distribution.’[40] Rhodes further decided that the additional items collected by the N.Z.E.F.’s War Trophy Officers, which were ‘curios’ rather than ‘trophies’, would also be sent to the regional War Trophies Committees for distribution, once the museums in the four main centres had selected suitable exhibits.[41] The long-awaited national distribution of trophies was now dependent upon the regional War Trophies Committees arriving at the most satisfactory method of evenly allocating these weapons within their respective districts. A major problem was that the new civilian members of these committees had no conception of what a war trophy looked like, and had to be guided by the military committee members, who were, in many cases, reluctant to become involved in local body politics.

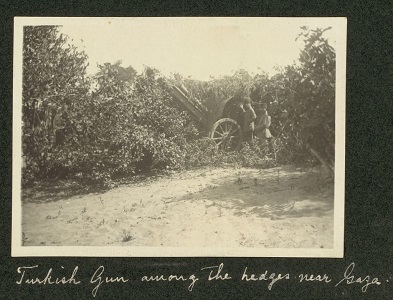

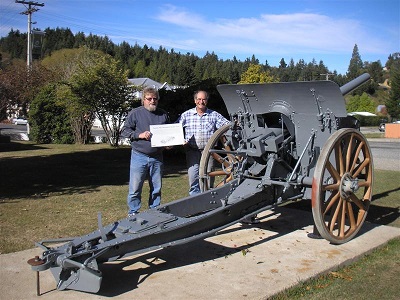

German 53mm anti-tank gun and pillbox

Some of the trophies stored at Trentham were discovered still to be potentially lethal. Two Privates, while toying with a German signal rocket about to be consigned to Wanganui, accidentally set it off, damaging the storage hut. The men were reprimanded, and one was required to pay for the damage, while a quantity of German munitions awaiting shipment as trophies was discovered to be both ‘live’ and ‘unstable’.[42] Despite this minor setback, General Richardson could report to the Minister of Internal Affairs in September 1920 that ‘the whole of the field guns have now arrived in the Dominion, and… should be distributed at an early date.’[43] Sir James Allen had claimed in September 1918 that New Zealand’s trophy distribution system was similar to those operating elsewhere in the Empire, but by September 1920 the allocation system was almost the exact opposite to those systems operating in England and Australia. While the British War Trophies Committee was primarily concerned with requirements of the Imperial War Museum, conversely the New Zealand War Museum Committee was preoccupied with the ‘equitable distribution’ of all trophies throughout the Dominion. Nevertheless, Sir Heaton Rhodes felt compelled to make a statement in the House, as ‘he was being so continually bombarded by questions with reference to the distribution of war trophies – by local bodies, private individuals and members of the House.’ Field guns, trench mortars and machine guns ‘would be allocated on a population basis’ by ‘District Committees, on which were represented the New Zealand Expeditionary Force, Returned Soldiers’ Associations (R.S.A), Mayors, and Chairmen of County Councils, Town Boards, and Road Boards’. Ten large German siege guns would be allocated to ‘the chief city in each of the provincial districts.’[44]

Mr J. R. Hamilton, the Member for Awarua, was not satisfied with Rhodes’ statement. His own electorate had not received any trophies, and as he ‘could see that there were a good many of the war trophies already distributed… he wanted justice done.’[45] Rhodes interpreted his question in the House as an indication that Hamilton wanted to represent his electorate on the local War Trophies Committee, and advised him to ‘keep off any such committees’ and thus save himself ‘a considerable amount of trouble.’.[46] Rhodes could speak with assurance, as the large siege guns (actually heavy German howitzers) had caused problems when Cabinet had decided to transfer one such gun from Wanganui to New Plymouth.[47] A public meeting in Wanganui condemned the decision, on the basis that ‘the fact that this town [Wanganui] had no standing as a provincial town should not be taken into consideration in a matter of this sort’, given that it was ‘the fifth largest town in New Zealand.’[48] Cabinet’s decision stood, however, and the Defence Department’s primary concern was that the siege guns ‘should be despatched to the various towns as soon as possible.’[49]

The Ordnance Department had been preoccupied with the sale of surplus equipment, but by 20 November 1920 all of the German machine guns had been packed and were ready for distribution.[50] The grand distribution of trophies was about to begin, and from November 1920 a steady stream of machine guns began to flow from the trophies store at Trentham.[51] The siege guns proved to be too big for the shipping companies to carry them fully assembled, and they had to be dismantled and reassembled under the supervision of Master Gunners in the ten provincial cities.[52] Field guns, trench mortars and machine guns proved to be easier to transport, and were either railed or shipped to their respective destinations between December 1920 and January 1921.

There were mixed reactions when the trophies arrived. Colonel T. W. McDonald, the Commander of the Otago Military District, did not appreciate the arrival in Dunedin of 78 packages of machine guns, with no indication from Trentham as to what was to be done with them.[53] The Invercargill City Council accepted siege gun number 359 ‘with thanks’, and placed it in front of the Government Buildings, directly opposite the Railway Station and in full view of anyone arriving in or departing from Invercargill by train.[54] The Dunedin City Council put its war trophies into storage pending a decision on how best to display them within the city.[55] The Vincent County Council did not receive any trophies, and asked Trentham for at least eight enemy weapons, as ‘throughout the County there are many children who have not the opportunity of visiting the larger centres where the most of the memorials of War are placed, and at present there is not one trophy from any war within the County.’[56]

The Wellington Military District had received a quantity of M.G. '08/15 machine guns, but they were missing their bipods, and in some cases their butts, which made them impossible to mount on display.[57] King’s College in Auckland discovered that its machine gun was ‘practically only a casing’ and attempted to obtain ‘the remainder of the gun otherwise the gift is useless.’[58] There were insufficient spare parts available for the machine guns, however, and the Defence Department decided that it was ‘more important to give good specimens [of machine guns] to colleges and schools than to local bodies.’[59] The reason for this decision was best expressed in the Ellesmere District School’s applications for a ‘Captured Machine Gun’. Having considered ‘the eminently educational and ever-memorial value’ of such a weapon, the school wanted a trophy to impress upon ‘each succeeding generation the value of [the] British Army and the Sense of Security attained by Victory’.[60]

The Ordnance Personnel at Trentham were obviously losing interest in the dilapidated enemy equipment which was causing them so many problems. The enemy munitions had been dumped at sea, the ‘uniforms and other textile materials’ had to be thoroughly disinfected, and the majority of machine guns were in a bad state of disrepair.[61] Late in 1920 the Army had undergone a major reorganisation which saw the Auckland, Wellington, Canterbury and Otago Military Districts replaced by the Northern, Central and Southern Military Commands. This reorganisation was accompanied by a further reduction in personnel, and by 1921 it was possible for files to be mislaid for three months at Defence Headquarters.[62] The War Trophies Store at Trentham now had only two men responsible for the storage and issue of the remaining trophies. Following a display of trophies in Wellington, General Richardson suggested that similar displays could be mounted ‘in various centres throughout the Dominion.’[63] A survey of the three Military Commands indicated that towns within the Southern and Central Commands supported the idea of a travelling display, while the various towns in the Northern Command, together with Auckland, received the suggestion ‘with little enthusiasm.’[64] Nevertheless, a travelling display of trophies was mounted in the Central Military Command in June 1921, under the supervision of Sergeant G. T. Dawson. As Dawson was the senior Non-Commissioned Officer In Charge of Trophies at Trentham, his absence meant that only Private McConkey was left in charge of the entire War Trophies Section. McConkey, ‘while generally competent in the duties required,’ could not cope with the correspondence which continued to arrive, and which was ‘for the most part of an urgent and important nature’.[65]

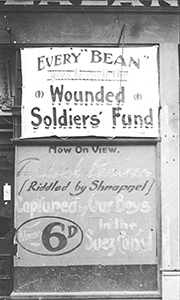

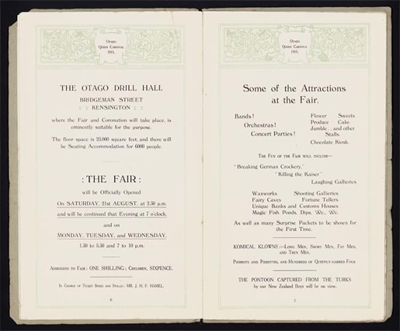

Sergeant Dawson, meanwhile, experienced problems with the touring exhibition. He had to unpack and display the exhibits and then lecture from 9.00 am to 10.00 pm daily, and received little assistance from local organisations with the running of the exhibition.[66] The display was well-attended in Hastings, where 7,525 adults and children viewed it, but the extremely cold weather, and the presence of counter-attractions such as the Gilbert and Sullivan Opera Company, meant that the exhibition was poorly patronised in Napier.[67] Dawson had to deal with further setbacks in Masterton and Palmerston North, where the show was poorly advertised, and as a result began to show a loss.[68] Attendance figures improved somewhat in Feilding and Dannevirke, and Colonel (previously acting Brigadier-General) C. W. Melvill, Commander of the Central Military Command, was impressed with Dawson’s ‘good appearance and address’, noting that he was ‘as keen as mustard on his job.’[69] These qualities, however, could not prevent the exhibition’s failure to attract crowds in the South Island, and after poor attendance figures in Christchurch and Kaiapoi the War Museum Committee decided that the ₤250,000 worth of exhibits should be returned to Trentham.[70]

Having received their field guns, howitzers, trench mortars or machine guns, many cities and towns were now trying to decide what to do with them. The Dunedin City Council, for example, positioned a siege gun and two field guns in front of the Boer War Memorial at the Oval, and placed a Turkish Pontoon in Woodhaugh Gardens, but was forced to return ‘a further 160 items of war material of a miscellaneous nature’ to the Kensington Army Drill Hall where the collection ‘could be more readily accessible to the public’.[71] The Council also had a large number of machine guns stored in the Town Hall, and the Reserves Section of the General Committee of the Council began to act as a local War Trophies Committee when the Council received applications for trophies from local schools. The Honorary Secretary of the North East Valley Public School Committee wrote to the Town Clerk in 1921 asking for a field gun, as the presence of such a weapon in the school grounds would ‘not only be furthering the cause of education but would help to keep ever-green in the minds of the children what the British Empire stands for… Justice, Liberty and Righteousness’.[72] The Reserves Committee allocated two machine guns to the school instead. The attitude of David Tannock, the Superintendent of Reserves, was that ‘modern guns are not suitable for setting-up outside, (except the very largest), they are ugly things at the best and unless constantly painted and greased would soon degenerate into a heap of iron.’[73] Mr R. S. Black, a future Mayor of Dunedin, objected to the Council giving trophies away to anyone who asked for them. He wished the Reserves Committee to consider that ‘the flower of our manhood went forth to uphold the honour of our Empire, and these trophies are worthy of better treatment than to be dispersed broadcast or thrown in the dust heap.’[74]

Some areas still did not have any trophies. The pattern of distribution indicated the importance given to New Zealand’s cities, towns and localities. Siege guns were given to the important provincial centres, field guns and trench mortars went to the cities and more important towns, while the large number of heavy (M.G. '08) and light (M.G. '08/15 and M.G.'08/18) machine guns were distributed between smaller towns and districts. It was of some concern to the Vincent County Council, therefore, to discover that it had been allocated only one field gun and four machine guns. The Council’s request for at least eight trophies had been ignored, prompting the County Clerk to turn for help to James Horn, the Member of Parliament for Wakatipu. The Council wanted a trophy for each riding so that those in ‘small villages’ could have the opportunity of viewing some of ‘the guns that were used in the Great War in which their brothers and relations took part’.[75] Horn, in turn, contacted Sir Heaton Rhodes, and explained that Vincent County had eight ridings and only five trophies. He asked Rhodes ‘to strain a point and supply them [the County Council] with three more machine guns and so get them out of trouble.’[76] Adam Hamilton, the Member for Wallace, also wrote to Rhodes, pointing out that the Wallace County Council, although the ‘most important’ in the Southland area, had not received a single trophy, while Riverton, Otautau and Winton had all received field guns.[77] Wallace County did finally receive a German 77 mm field gun as requested, even if Defence Headquarters in Wellington did not know the different between Winton and Otautau when consigning it![78]

A separate distribution of trophies occurred in Wellington in the middle of 1921. Following a suggestion by General Richardson, a selection of captured German Mauser rifles, steel helmets and shell cases were issued to seven Cabinet Ministers, sixteen Private Secretaries and Under-Secretaries, and six officers from Defence Headquarters.[79] This issue of trophies came to the attention of J. O’Donovan, the Commissioner of Police, who informed Richardson that ‘Section 7 of the Arms Act, 1920, provides that no person shall procure possession of a firearm unless he has a permit issued to him by an officer of police authorised in that behalf, and that no person shall deliver a firearm to any person unless the latter has a permit.’[80] The Police Department was supplied with a list of those who had received rifles, and asked the recipients to register their trophies. Evidently these weapons were of greater concern to the Police than the 1,500 machine guns recently distributed throughout the country, as no attempt was made to regulate the ongoing issue of machine guns from the War Trophies Store at Trentham.

By the end of 1921, the majority of war trophies had been issued, and siege guns, howitzers, field guns and trench mortars were on display in most of New Zealand’s cities and towns. Townships and small districts, together with schools, universities, public libraries and R.S.A. clubrooms, all had German machine guns in varying states of disrepair, either on display or in storage.[81] Where they were on public display, such war trophies were usually positioned on or beside the nation’s newly-constructed war memorials.[82] In a country still grieving for its war dead, no-one thought that German weapons were out of place beside memorials ‘fashioned… in stone.’[83] Some trophies, however, were given a new significance, as in Christchurch where two field guns and a siege gun were placed in front of the Supreme Court as if to “uphold the law"?.[84] In Invercargill, artillery pieces were placed in front of the Government Buildings, the Post Office and the Water Tower, while Tapanui sited its trench mortar right in the centre of the township.[85]

The realities of the post-war world and the ‘mini-depression’ of the early 1920s meant that the question of an ‘equitable distribution’ of war trophies was soon replaced by more pressing political issues. At the same time, the Army faced a severe shortage of personnel and a reduced budget, although the Chanak Crisis in 1921 prevented any further decline in New Zealand’s Defence Forces.[86] In 1923, General Richardson left New Zealand to become the administrator of Western Samoa, by which time only a handful of field guns remained at the Army’s Te Aro store in Wellington, still awaiting their collection by the Dominion Museum.[87] War trophies evidently became an accepted part of the New Zealand landscape, once the brief period of nationalistic fervour had died down. Without a National War Museum the New Zealand public still had little idea of what the members of the N.Z.E.F. had actually experienced, and the R.S.A. Journal Quick March expressed the bitterness felt by returned servicemen at ‘the lack of recognition and practical help [from the public] following their return from the First World War’.[88] Oblivious to these changes in New Zealand society, the German weaponry on display throughout the Dominion continued to mount a silent guard over the memorials to those who had died in the Great War, the country’s only tangible means of illustrating to future generations exactly what had been lost and won in the Great War.

References:

1. Brigadier-General G. S. Richardson, Wellington, to the Director of Equipment and Ordnance Services, Wellington, 3 July 1919, in AD1 762 19/41/1 Part 1.

2. Brigadier-General G. S. Richardson, Wellington, to Major-General A.W. Robin, Wellington, 22 July 1919, AD1 763 19/45.

3. Major-General A. W. Robin, Wellington, to J. Allen, Wellington, 23 July 1919, in ibid.

4. Note appended by J. Allen, 11 August 1919, to Major-General A.W. Robin, Wellington, to J. Allen, Wellington, 23 July 1919, in ibid.

5. J. Hislop, Under-Secretary of Internal Affairs, Wellington, to Major-General A. W. Robin, Wellington, 5 September 1919, in ibid; Lieutenant H.T.B. Drew, Officer in Charge, War Records, Wellington to Brigadier-General G.S. Richardson, Wellington, 8 August 1919, in AD1 762 19/41/1 Part 1.

6. “Record of the Proceedings of a Meeting of the War Museum Committee held on 11 September 1919 at Defence Headquarters"?, in AD1 763 19/45.

7.The Mayor, Wellington City Council, to J. Allen, 3 July 1919; N.Z.E.F. Headquarters, London, to Defence Headquarters, Wellington, 14 August 1919 and note appended by Major-General A.W. Robin, 18 August 1919, all in AD1 762 19/41.

8.Lieutenant H. T. B. Drew, Wellington, to Brigadier-General G. S. Richardson, Wellington, 3 November 1919, in AD1 973 19/45; Lieutenant H. T. B. Drew, Wellington, to Brigadier-General G.S. Richardson, Wellington, 8 August 1919, in AD1 762 19/41.

9.Brigadier-General G. S. Richardson, ‘General Headquarters Instruction No .54, 12 August 1919’, in AD1 762 19/41/1 Part 1.

10.Mr G. J.Anderson (Mataura), question to the Hon. Sir J. Allen (Minister of Defence), 9 September 1919, in New Zealand Parliamentary Debates (hereafter NZPD), Volume 184, p. 338.

11.Reply by the Hon. Sir J. Allen 9 September 1919, in ibid.

12.Mr Parr (Eden), question to the Hon. Sir J. Allen, 17 September 1919, NZPD, Volume 184, p. 601.

13.Reply by The Hon. Sir J. Allen, 17 September 1919, in ibid.

14.J. Hislop, Wellington, to the Minister of Internal Affairs, Wellington, 6 October 1919, in AD1 762 19/41/1 Part 1.

15.Lieutenant H. T. B. Drew, Wellington, to Brigadier-General G.S. Richardson, Wellington, 3 November 1919, AD1 763 19/45.

16.Lieutenant-Colonel J. Sleeman, Director of Military Training, Wellington, to Lieutenant V. G. Jervis, Officer in Charge of War Records and Trophies, Wellington, 25 November 1919, in ibid.

17.Lieutenant-Colonel H. E. Avery, ‘Q’ Duties, Wellington, to The Staff Officer in Charge, ‘A’ Branch, Wellington, 24 November 1919, in AD 1 762 19/41/1 Part 1.

18.Lieutenant A. J. Ridler (for Brigadier-General G. S. Richardson), Wellington to Lieutenant V.J. Jervis, Wellington, 22 December 1919, in ibid.

19.Pugsley, Gallipoli, pp. 350-2.

20.P. J. Wilkie, Keeping Faith with the Dead: War Memorials in the Dunedin Area, Department of History, University of Otago, Dunedin 1983, .Introduction, p. 1.

21.“Applications for War Trophies"? (undated), in AAYS 8368 AD1 762 19/41/3 Part 1 ‘Competitions and Trophies - Trophies, War, Allocation and Distribution of, 1922 – 1945’ (R22430288) (hereafter AD1 762 19/41/1 Part 1), held at Archives NZ, Wellington.

22.A quotation from a resolution passed by the National War Memorial Committee in 1920, in Wilkie, Keeping Faith with the Dead, p. 4.

23.Lieutenant V. G. Jervis, Wellington, to Defence Headquarters, Wellington, 13 January 1920, in AAYS 8368 AD1 762 AD 19/41/1 Part 2 ‘Competitions and Trophies - Trophies from the Front. Presentation of to the N.Z. Government, 1920’ (R22430289) (hereafter AD1 762 19/41/1 Part 2), held at Archives NZ, Wellington.

24.Lieutenant V. G. Jervis, Wellington, to Defence Headquarters, Wellington, 3 February 1920, in ibid.

25.G. Mair, Ohinemutu, Rotorua to Lieutenant V.G. Jervis, Wellington, 9 March 1920; Colonel T.W. McDonald, Commander, Otago Military District, Dunedin to Defence Headquarters, Wellington, 10 May 1920, both in ibid; T. R. Palmer, Town Clerk, Wellington City Council, to J. Allen, Wellington, 19 June 1920, in AAYS 8368 AD1 763 19/41/7 ‘Competitions and Trophies - Trophies, War, Wellington City Council, 1917 – 1938’ (R22430298) (hereafter AD1 763 19/41/7), held at Archives NZ, Wellington.

26.For instance the Invercargill City Council decided in February 1920 to erect a war memorial - see J. O. P. Watt, Centenary of Invercargill Municipality, 1871-1971, Invercargill, 1971. p. 166; Wilkie, Keeping Faith with the Dead, p. 5; Lieutenant-Colonel H. E. Avery, Wellington, Memorandum for all District Headquarters, 12 February 1920, in AD1 762 19/41/1 Part 2.

27.Wilkie, Keeping Faith with the Dead, p. 15.

28.G. S. Scholefield, Who’s Who in New Zealand and the Western Pacific 1925, Masterton, 1924, pp. 3-4.

29.Mr E. Newman (Manawatu), question to the Hon. J. G. Coates (Minister of Defence), 29 June 1920, in NZPD, Volume 186, p. 11.

30.Reply by the Hon. J. G. Coates 29 June 1920, in ibid.

31.H.T.B. Drew, ‘War Finance’, in Drew (ed.), The War Effort of New Zealand, pp. 241-2.

32.Brigadier-General G. S. Richardson, Wellington, to J. Allen, Wellington, 16 April 1920, in AD1 762 19/41/1 Part 2.

33.“War Museum Committee. Minutes of Fourth Meeting, 18 June 1920"?, in AD1 763 19/45.

34.Dr J. A. Thomson, Director, Dominion Museum, Wellington, to the Minister of Internal Affairs, Wellington, 15 April 1920, in ibid; Brigadier-General G.S. Richardson, President, War Museum Committee, Wellington, to the Minister of Internal Affairs, Wellington, 24 June 1920, in AD1 762 19/41/1 Part 2.

35.Dr J. A. Thomson, Wellington, to Brigadier-General G.S. Richardson, Wellington, 9 April 1920; Dr J.A. Thomson, Wellington to Brigadier-General G.S. Richardson, Wellington, 18 June 1920, both in AD1 762 19/41/1 Part 2.

36.Brigadier-General G. S. Richardson, Wellington, Memorandum to Commanders, All Districts, 27 July 1920, in AAYS 8368 AD1 762 19/41/2 ‘Competitions and Trophies - Trophies from the Front. Presentation of to the N.Z. Government, 1920’ (R22430291) (hereafter AD1 762 19/41/2), held at Archives NZ, Wellington.

37.Brigadier-General G. S. Richardson, Chairman, War Museum Committee, Wellington, to the Minister of Internal Affairs, Wellington, 27 July 1920, in ibid.

38.Colonel R. Young, Commander Canterbury Military District, Christchurch, to Defence Headquarters, Wellington, 30 July 1920; Colonel H. R. Potter, Commander, Auckland Military District, Auckland, to Defence Headquarters, Wellington, 30 July 1920; Colonel C. W. Melvill, Commander, Wellington Military District, Palmerston North, to Defence Headquarters, Wellington, 2 August 1920; Colonel T. W. McDonald, Dunedin, to Defence Headquarters, Wellington, 18 August 1920, all in ibid.

39.Mr Burnett (Temuka), question to the Hon. Sir R. H. Rhodes (Minister of Defence), 11 August 1920 in NZPD, Volume 187, pp. 111-2.

40.Reply by the Hon. Sir R. H. Rhodes 11 August 1920 in ibid.

41.The Hon Sir R. H. Rhodes, Wellington to J. A. Nash, MP for Palmerston North, Wellington, 12 August 1920, in AD1 762 19/41/2.

42.Captain H. H. Whyte, Ordnance Officer, Trentham to the Chief Ordnance Officer, Wellington, 23 August 1920, in ibid.

43.Brigadier-General G. S. Richardson, Chairman, War Museum Committee, Wellington to J. Anderson, Minister of Internal Affairs, Wellington, 6 September 1920, in ibid.

44.The Hon. Sir R. H. Rhodes, Statement to the House, 8 September 1920, in NZPD, Volume 187, pp. 706-7.

45.Mr J. R. Hamilton (Awarua), question to the Hon. Sir R.H. Rhodes, 14 September 1920, in NZPD, Volume 187, p. 888.

46.The Hon. Sir R. H. Rhodes, 14 September 1920, in ibid.

47.Brigadier-General G. S. Richardson (for Major-General E. W .C. Chaytor, Commandant, New Zealand Military Forces), Wellington, to The Hon Sir R. H. Rhodes, Wellington, 14 October 1920, in AD1 762 19/41/2.

48.Lieutenant-Colonel W. H. Cunningham, Chairman, No.20 Group, War Trophies Committee, Wanganui, to The Hon Sir R. H. Rhodes, Wellington, 2 November 1920, in ibid.

49.Brigadier-General G. S. Richardson, Wellington, to The Hon Sir R.H. Rhodes, Wellington, 12 November 1920, in ibid.

50.Lieutenant-Colonel H. E. Pilkington, Director of Ordnance Services, Trentham, to Defence Headquarters, Wellington, 20 November 1920, in ibid.

51.“Schedule of Issues of War trophies"?, undated (circa October 1927), in AAYS 8368 AD1 762 19/41/3 Part 1 ‘Competitions and Trophies - Trophies, War, Allocation and Distribution of, 1922 – 1945’ (R22430288) (hereafter AD1 762 19/41/3 Part 1), held at Archives NZ, Wellington.

52.Lieutenant-Colonel R. B. Smythe, ‘G’ Duties, Wellington, Memorandum for Commanders All Districts, 23 December 1920, AD1 762 19/41/2.

53.Colonel T. W. McDonald, Dunedin, to Defence Headquarters, Wellington, 4 January 1921, in AAYS 8368 AD1 762 19/41/3 ‘Competitions and Trophies - Trophies from the Front. Presentation of to the N.Z. Government, 1921’ (R22430292) (hereafter AD1 762 19/41/3), held at Archives NZ, Wellington.

54.Mr F. Burnwell, Town Clerk, Invercargill, to The Hon Sir R. H. Rhodes, Wellington, 10 February 1921, in ibid.

55.‘Reserves Committee Report 1920-1921’, in Dunedin City Council Departmental Reports 1920-1921, p. 106, held at the Dunedin City Council Archives (hereafter DCC Archives), Dunedin.

56.Mr R. M. Ray, County Clerk, Vincent County Council, Clyde, to Captain H. H. Whyte, Trentham, 10 February 1921, in AD1 762 19/41/3.

57.Lieutenant-Colonel J. H. Whyte (for Commander, Central Military Command), Palmerston North, to Defence Headquarters, Wellington, 4 March 1921, in ibid.

58.Colonel H. R. Potter, Auckland, to Defence Headquarters, Wellington, 7 March 1921, in ibid.

59.Lieutenant-Colonel R. B. Smythe (for Brigadier-General G. S. Richardson), Wellington, to Colonel H.R. Potter, Auckland, 10 March 1921; Lieutenant-Colonel H. E. Pilkington, Trentham, to Captain H. H. Whyte, Trentham, 14 March 1921, both in ibid.

60.Mr M. D. Doubleday, Ellesmere District School, to the County Clerk, Springs County Council, 27 April 1921, in ibid.

61.Captain A. E. Nelson, Wellington, to the Chief Ordnance Officer, Trentham, 3 November 1920, in AD1 762 19/41/2; Brigadier-General G. S. Richardson, Wellington, to the Director of Munitions and Ordnance, Wellington, 26 February 1921; Captain H.H. Whyte, Acting Chief Ordnance Officer, Trentham to Lieutenant-Colonel H.E. Pilkington, Trentham, 18 April 1921, both in AD1 762 19/41/3.

62.Lieutenant-Colonel H. E. Pilkington, Trentham to Headquarters, Southern Military Command, Christchurch, 4 June 1921,in AD1 762 19/41/3.

63.Brigadier-General G. S. Richardson, Wellington to The Hon Sir R. H. Rhodes, Wellington, 23 March 1921, in AAYS 8368 AD1 764 19/70 ‘Competitions and Trophies - Trophies, War, Exhibition throughout N.Z., 1921 – 1922’ (R22430318) (hereafter AD1 764 19/70), held at Archives NZ, Wellington.

64.Lieutenant-Colonel H. E. Pilkington, Trentham, to the Chief Ordnance Officer, Trentham, 5 June 1921; Colonel C. W. Melvill, Palmerston North, to Defence Headquarters, Wellington, 26 May 1921; Colonel H.R. Potter, Auckland, to Defence Headquarters, Wellington, 19 May 1921, all in ibid.

65.Captain H. H. Whyte (for Chief Ordnance Officer), Trentham, to Lieutenant-Colonel H. E. Pilkington, Wellington, 6 July 1921, in ibid.

66.Sergeant G. T.Dawson, “Report on Exhibition at Masterton, 27 July – 3 August 1921"?, undated ((? August 1921), in ibid.

67.Sergeant G. T. Dawson, “Report on Exhibition at Hastings"?, undated, ((?) July 1921; J. M. Brown, Secretary, Napier City Board and St John Ambulance Brigade, to Lieutenant Colonel R .B. Smythe, ‘G’ Duties, Wellington, 22 July 1921, both in ibid.

68.Sergeant G. T. Dawson, “Report on Display at Palmerston North, 11 – 18 August 1921"?, undated, ((?) August 1921), in ibid.

69.Lieutenant-Colonel R. B. Smythe, ‘G’ Duties, Wellington, to Headquarters, Central Military Command, Palmerston North, 19 August 1921, in ibid.

70.Colonel R. Young, Christchurch, to Defence Headquarters, Wellington, 14 December 1921; Brigadier-General G.S. Richardson, Wellington to Colonel R. Young, Christchurch, 15 December 1921, both in ibid.

71.‘Reserves Section of the General Committee Report 1921-1922’, in Dunedin City Council Departmental Reports 1921-1922, pp. 61-2, held in DCC Archives, Dunedin.

72.Mr J. J. Bardsley, Honorary Secretary, North East Valley Public School Committee, Dunedin, to Town Clerk, Dunedin, undated (circa November 1921), in ‘D.C.C. T.C. 33, 1921, Finance W/2’, held in DCC Archives, Dunedin.

73.‘List of Trophies Issued by the Dunedin City Council’, undated (circa December 1921); D. Tannock, Superintendent of Reserves, Dunedin City Council, Minute Paper, 19 September 1921, both in ibid; K./ C. McDonald, City of Dunedin, A Century of Civic Enterprise, Dunedin, 1965, p. 257.

74.Mr R. S. Black, Dunedin, to the Chairman, Reserves Committee, Dunedin City Council, 1 September 1921, in D.C.C. T.C. 33, 1921, Finance W/2.

75.Mr R. M. Ray, County Clerk, Vincent County Council, Clyde, to Mr J. Horn, Member of Parliament for Wakatipu, Dunedin, 4 June 1921, AD1 762 19/41/3.

76.Mr J. Horn, Dunedin, to The Hon Sir R. H. Rhodes, Wellington, 15 June 1921, in ibid.

77.Mr A. Hamilton, Member of Parliament for Wallace, Winton, to The Hon Sir R. H. Rhodes, Wellington, 15 June 1921; Mr J. G. C. Baker, County Engineer, Wallace County Council, Otautau, to A. Hamilton, Winton, 28 June 1921, both in ibid.

78.A. Hamilton, Winton, to The Hon Sir R. H. Rhodes, Wellington, 15 August 1921, in ibid.

79.Brigadier-General G .S. Richardson, Wellington, to The Hon Sir R. H. Rhodes, Wellington, 15 March 1921; Brigadier-General G.S. Richardson, Wellington to the Inspector of Police, Police Headquarters, Wellington, 20 September 1921, both in AAYS 8368 AD1 763 19/41/216 ‘Competitions and Trophies - War Trophies, Issue of to Cabinet Ministers and Private Secretaries, 1921’ (R22430294) (hereafter AD1 763 19/41/216), held at Archives NZ, Wellington.

80.J. O’Donovan, Commissioner of Police, Wellington to Brigadier-General G.S. Richardson, Wellington, 18 August 1921, in ibid.

81.“Schedule of Issues of War Trophies"?, undated (circa October 1927), AD1 762 19/41/3 Part 1.

82.A number of World War One trophy guns may still be seen beside war memorials. As at September 1987, the following German-made artillery pieces were still in position:

Arrowtown: A Turkish 75 mm Modell 1903 field gun, stamped ‘7th Light Horse, New South Wales’. Photographed 18/1/87, War

Trophies Albums Volume 1, Author’s Collection.

Cromwell: A German 77 mm F.K. ’16, Number 25261. Photographed 23/11/86, in ibid.

Maheno: Nichols’ Estate, Kuriheka – A German 77 mm C96 n/A, Number 9419, a German 24.5 cm Minenwerfer, Number 3674, a German 7.5 cm Minenwerfer, Number unknown, and a Turkish 75 cm field gun, stamped ‘1/1 WORCESTER YEO. MUSEUM, WORCESTER’. Photographed 18/11/86, War Trophies Albums Volume 2, Author’s Collection.

Naseby: A German 77 mm F.K. ’16, Number 11746. Photographed 24/11/86, in ibid.

Otautau: A German 77 mm C 96 n/A, Number 13262, and a Turkish 75 mm Modell 1903 field gun. Photographed 15/2/87, in ibid.

83.Pugsley, Gallipoli, p. 354.

84.Photograph showing three German Artillery pieces outside the Christchurch Supreme Court (undated), with the caption: ‘These guns outside the Supreme Court, Christchurch, were sent to Burnham in 1941’, in Photograph Series 350, World War Two (no negative), held at the ATL, Wellington.

85.Watt, Centenary of Invercargill, p. 157. Tapanui: a German 24 cm Albrecht Flugel Minenwerfer, Number 121, Photographed 13/12/86, in, War Trophies Albums Volume 2, Author’s Collection.

86.Barber, Red Coat to Jungle Green, pp. 97-9.

87.Scholefield, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, Volume II, p. 234. Major E. Puttick, New Zealand Staff, ‘Q’ Duties, Wellington, to Lieutenant-Colonel H.E. Pilkington, Trentham, 10 March 1923; Mr A. Ridler, Secretary, War Museum Committee, Wellington, to Major-General E. W. C. Chaytor, Wellington, 24 October 1923, both in AD1 762 19/41/3 Part 1.

88.Wilkie, Keeping Faith with the Dead, p. 28.